Chinese divination is a really complex and syncretistic practice. There’s just so many different schools of thought, so many various ideologies that are not competing but layered over one another.

The most basic building block of Chinese divination is the taiji image—yin and yang.

You’ve seen this image before whether that’s on stoner paraphernalia, the South Korean flag, or martial arts class advertisements. It’s a picture of a circle, half black and half white. There’s a white dot in the black half and a black dot in the white half.

A lot of people have a lot to say about this image. Yin and yang has been reconstructed as ideological war, as remediation, and even as abolition. Usually, you find a lot of New Age type people in the West describe yang as the active or male principle and yin as the female or passive principle. I invite you to rethink this diagnosis. Beginning with gender when understanding yin and yang is distracting and misses the point of the concept. A lot of descriptions of yin and yang are made by people who don’t actually know Chinese or any Asian language.

This is what yin and yang are: yin is the moon and yang is the sun. That’s it. That’s all it is.

Alternatively—and this makes things a bit more complicated—yang is the sun and yin is the absence of the sun. Let me explain why.

The traditional word for yinyang is 陰陽. The 阝 radical refers to 阜. You can think of it as like a flag marking a mound to denote a place. 陰 is yin and the other part of the character, 侌, is shadow. If you break this part of the character down further, you’ll see that it’s the character for day (今) over the character for cloud (云). 陰 or yin is just cloudy day. 陽 is yang and 昜 is a picture of the sun with rays emanating out. 昜 is very similar to the character that is used in 易經 or Yi Jing/I Ching which is the Book of Changes. The changes being talked about are the changes of the sun.

After revolution, 陰陽 was simplified to 阴阳. There are also a couple of instances of 阴阳 being used in place of 陰陽 in older texts. 阴阳 is really simple. 月 is just moon and 日 is sun. Yinyang becomes the moon and the sun. 日 is also the word for day and 月 is the word for month. Yinyang also expresses measurements of time.

Why do I think that discussing yinyang using gender confuses people? Because gender is already a social construction. Let’s ignore gender altogether for the moment and just take yinyang as a cosmological principle and see what happens.

The concept is actually already pretty complicated. Yinyang is the sun and moon. It’s also the sun and the absence of light. On top of that, because the sun rises and sets everyday while a lunar cycle takes a month, it’s an expression of time.

The 滴天髓, The Dripping Marrow of Heaven, is a series of ancient scriptures about divination. It opens with yinyang. It tells us that the cosmos has yin and yang, that this creates the five phases, and that divination is the art of perceiving the three destinies—cosmic, nature, and human. More specifically, it tells us that we have to find the core of every shifting circumstance. This is divination as perception.

That’s why it’s important to consider yinyang as a concept about light—because it’s about perception.

The world that Chinese divination describes is a world that is lit by sunlight and moonlight. What happens if you don’t have any sunlight or moonlight? You can’t see anything. Everything disappears. This is why everything in the world has yin and yang—because nothing can exist unless it is revealed through either sunlight or moonlight. This is if you want to think about yinyang as sun and moon. If you prefer to think about it as light and shadow, you can say that everything in the world is either visible or invisible. Those are the only two options when we talk about perception. Either something is in your perception or it isn’t.

Already, we have some meanings for yin and yang. Yin is night and yang is day. Yin is also north since Chinese divination is northern hemisphere based and yang is south. Yin is winter for the same reasons and yang is summer. This is about proximity to and distance from the sun.

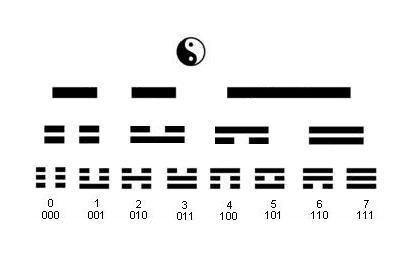

Usually, yin is represented by a broken line (⚋) while yang is represented by an intact line (⚊). These two principles then create four images: ⚌, ⚏, ⚍, and ⚎.

⚌ is old yang and ⚏ is old yin. You can think of them as summer/noon or winter/midnight. You’re going from a time that is already quite yang like the spring or morning into a time that is more yang (taiyang or old yang). Or, you’re going from a time that is already yin like the fall or evening into a time that is deeply yin (taiyin or old yin).

⚍ is young yin. This is the fall or evening. It’s the time when yin starts to overcome yang. ⚎ is young yang. It’s when yang starts to overcome yin which happens in the morning or spring.

Now we have four images created by the two principles of yin and yang. We have yin changing into yang, yang changing into yang, yang changing into yin, and yin changing into yin. We begin with the two types of light, either sunlight and moonlight or light and no light, and we end up with four possible conditions of light.

Let’s add one more line. We’ll get eight combinations. This is called the bagua or 八卦. Two principles become four images which become eight symbols or trigrams.

This is where things start to get interesting. The bagua expresses family structure, social roles, seasonal cycles, and the five processes. The bagua has two arrangements and both of these arrangements give us different information. This is also where I’ll leave you since this is an introductory post. You’ll hear from me again about this subject. Until next time.

1 of 19

>>>